Click to Enlarge +

|

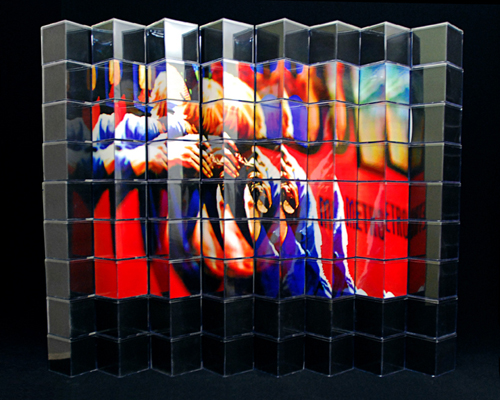

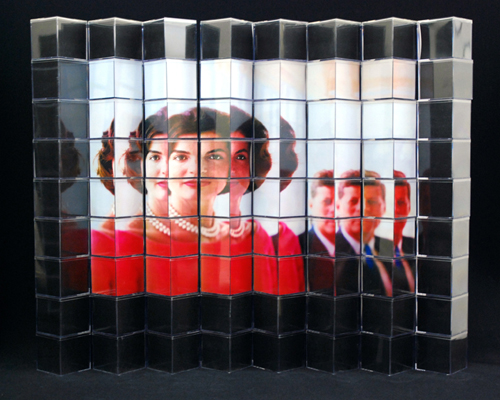

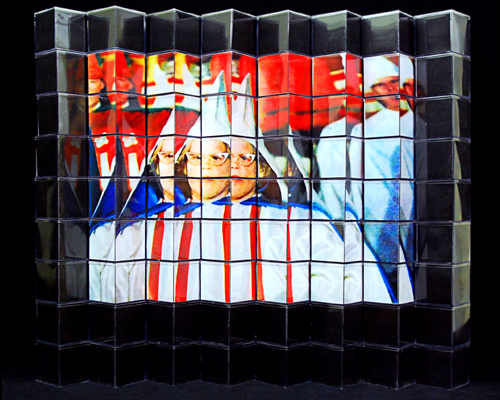

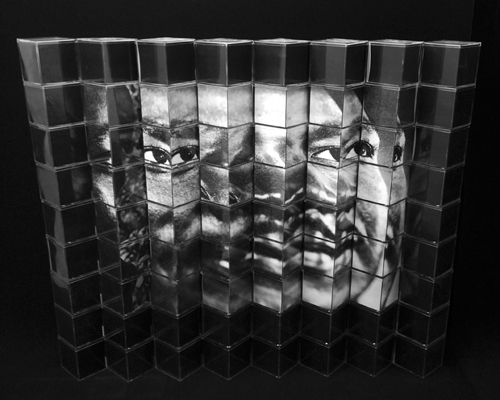

Combining his fascination with picture making, history, and curating, Robert Hirsch's The Sixties Cubed is a sculptural anthology based on photographic reinterpretations of historic and personal images covering an epoch between the late-1950s through the early 1970s. It is the culmination of three years of research, which utilizes the camera to re-envision the competing social landscapes that shaped the American zeitgeist of that decade. Thousands of the resulting pictures, curated from a database of over 40,000 images, are presented in clear, 4 x 4 x 4-inch stackable cubes, which resemble the popular Kodak Instamatic photo cubes from that era.

On describing the project Hirsch comments, "No decade in recent U.S. history has reverberated and been mythologized more than the 1960s. This venture explores how visual media interact with the exceptional and everyday cultural/economic/political/scientific realms...My purpose is not one of historical archivist or nostalgia, but rather to visually stimulate viewers to connect the past and the present to ponder the future. History forms our national identity and affects how we view the world. In this sense, this project offers a visual representation of our collective societal memory of those times. It produces an open, wordless storytelling format and encourages viewers to ponder how this decade affects who we are today.

ABOUT THE BOOK

The 1960s Cubed: A Counterculture of Images by Robert Hirsch

This catalog presents The 1960s Cubed exhibition, a photographic, sculptural anthology and historic narrative of the late-1950s through the early 1970s. Utilizing a post-documentary approach of freshly seeing and interpreting historical images, the installation imaginatively re-envisions the competing social landscapes that shaped the American zeitgeist of the decade. Echoing the Kodak Instamatic photo cube, the thousands of resulting photographs are presented in clear, 4 x 4 x 4-inch stack-able cubes form montages, sculptural structures, and individual compound portraits.

The project’s title addresses amplification in number and possibilities, underscoring how creation and meaning are personal and in flux. Using fragments to invent new forms, allows the re-seen photographs to transcend their original intent, making each image alive with fresh potential. Generating a space between history, media narrative, and database, this project combines a lineage in experimental films from Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929) to Christian Marclay’s The Clock (2010) with Cubism and Pop Art. It breaks with linear illustration to reveal the paradoxes and puzzles of memory construction, evoking a visceral and emotional point of discovery that asks one to dig deeper and discover a personal telling. As Oscar Wilde remarked: “The moment you think you understand a work of art, it’s dead for you.” Thus, The 1960s Cubed highlights how images from the past can be supple entities, upon which fresh interpretation can expand one’s historic sensibility by revealing new commentary.

1960s Project Description

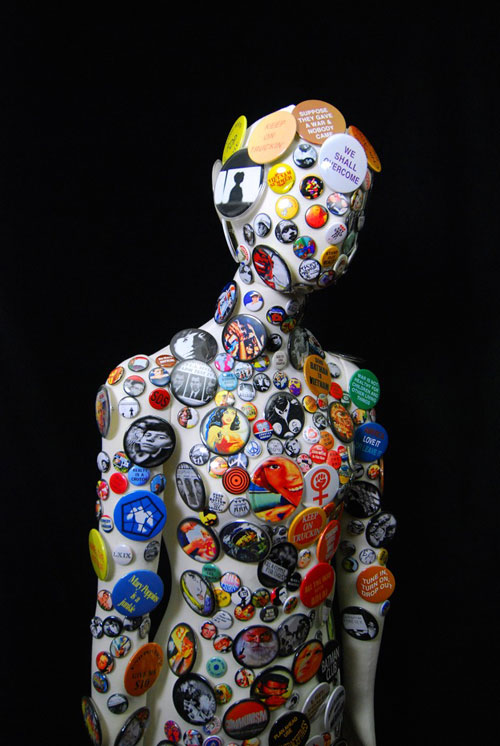

Combining my fascination with picture making, history and curating, The 1960s Cubed is a sculptural anthology based on photographic reinterpretations of historic and personal images covering an epoch between the late-1950s through the early 1970s. It is the culmination of three years of research, which utilizes the camera to re-envision the competing social landscapes that shaped the American zeitgeist of that decade. Thousands of the resulting pictures, curated from a database of over 25,000 images, are presented in clear, 4 x 4 x 4 inch stackable cubes, which resemble the popular Kodak Instamatic photo cubes from that era. The complete installation features:

• Cube montages in gallery windows

• 8 double-sided 30 x 40 inch compound portraits assembled from individual image blocks

• A flexible, life-sized mannequin covered with 60s buttons

• An 8 x 40 foot image timeline

• A rotating, 5-foot, two-fingered peace sign covered with images

• A 5-foot, frustum (split), walk through, image cube pyramid

• A mini-theater that projects transparent images from a modified 1960 Brion Gysin Dream Machine, which utilizes the “flicker” effect to produce colors and visions

• A 60s audio soundtrack

• Psychedelic exhibition poster

Why the 1960s?

It’s problematical to reflect on a moving target, a work that is still in progress, but my essential role is one of witnesses, chronicler, and artist. No decade in recent U.S. history has reverberated and been mythologized more than the 1960s. This venture explores how visual media interact with the exceptional and everyday cultural/economic/political/scientific realms. It offers a kaleidoscope of pictures of a time I experienced and recorded as a budding photographer in the New York City area. Additionally, it juxtaposes how demographics of Baby Boomers, those born approximately between 1946 and 1960, challenged the traditional values of the “Silent Majority.” My purpose is not one of historical archivist or nostalgia, but rather to visually stimulate viewers to connect the past and the present to ponder the future. History forms our national identity and affects how we view the world. In this sense, this project offers a visual representation of our collective societal memory of those times. It produces an open, wordless storytelling format and encourages viewers to ponder how this decade affects who we are today.

Defining the 1960s

The Sixties, regardless of your political persuasion, was a time of extreme polarity. On one hand there was John F. Kennedy’s New Frontier with its sense of idealist public service including the Peace Corps, the physical fitness program, and the challenge to place a man on the moon. The Civil Rights Movement culminated with the March on Washington and Martin Luther King’s “I Have A Dream” speech. This led into Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society that implemented the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act as well as environmental and consumer protections. It was a period of middle-class, economic expansion, accompanied by an outburst of consciousness-expanding energy that led to experimentation in the arts, culture, and politics. Creative individuals were recognized in the media and portrayed as pathfinders searching for enhanced consciousness and heightened potentials. Women and minorities confronted societal standards to build a more humane and open society with expanded personal freedoms.

Conversely, there were the assassinations of John Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Robert Kennedy plus the murders of African-Americans, and civil rights workers. President Johnson’s escalation of the Vietnam War resulted in civilian and military casualties estimated at 2,500,000 people. Inner city riots and antiwar protests took place along with hedonistic and nihilistic extremes as exemplified by Altamont and the Charles Manson Family murders. It was also an era of Thalidomide babies, the Bay of Pigs, the Cuban Missile Crisis, Missile Gaps, and above ground testing of nuclear weapons, all of which took the world to the edge of “Mutual Assured Destruction” (MAD). Finally, the 60’s marked the beginning of a long, downhill spiral of faltering public confidence in the ability of Big Government (aka Liberal Democrats) to make things work correctly and honestly.

Although its legacy is hotly debated, there was an intense drive to generate alternatives in how cultural institutions operated that defined the 1960s. That said, my intention today is to discuss just a few of the project’s key artistic and conceptual underpinnings with the intent of encouraging viewers of all political and social persuasions to rethink the 1960s and how it continues to affect American culture and politics.

Art as a Transformative Practice

This project is based in archeology, an examination of history through the excavation of visual artifacts. It embraces what working artists know – our cultural heritage is founded on a practice of transformative art. This originates within our cultural commons, the vast store of ideas inherited from the past, which informs the present, and can be utilized to enrich the future.

In our point-and-click culture, any data we Google can provide an initial matrix for new creations involving mash-ups, remixes, and sampling. Is there any difference between photographing a building or a web page? Both exist as completed constructions and as potential raw material for resourceful directions. The more we know about how art is made, the more derivative and evolutionary we recognize art to be. Innovative artists think, imagine, and express notions differently from previously recognized views of a similar subject. Hence, thoughtful picture making is an act of authentic assertion, control, and organization over a subject. Each generation of inventive imagemakers confront the same challenge: how to make memorable pictures of their times. What is vital is not where you take things from, but where you take them to. Digital society thrives on this beehive of information and the recognition that all is ours, and nothing is ours.

Use of Multiples

The project’s theoretical framework is rooted in the Greek philosophical premise that nothing comes from nothing and in turn things do not disappear into nothing, but rather are transformed into something else (ex nihilo nihil fit). It acknowledges that everything precedes us; that we absorb the materials and the tools that compose who we are, making appropriation a universally open secret.

Our western capitalist models are predicated on copies, duplicates, multiples, replicas, the mass production and circulation of useful identical products. This was also a driving force behind the invention of photography, creating a matrix capable of striking copy after copy.

We learn and are inspired by studying the examples of others. Often they say something that we immediately identify with, but could not express until we came into contact with that work. We come to SPE conferences in hopes of encountering something that will offer us insights and/or directions in our work. This is the transformative process at work. Select any artistic practice and you will find this progression of observation, accessing, mixing, and innovation. Ultimately, copies are us.

Image Treatment

The project’s inventory of 25,000 images involved three years of visual research that concentrated on images in the public realm, acquired from publications including Avant Garde, Ebony, Life, Look, The New York Times, Newsweek, Playboy, Popular Mechanics, Popular Science, Ramparts, The Saturday Evening Post, Time, and Vogue. Additional image sources include high school yearbooks, the Internet, and photographs I recorded from that era.

The image selection reflects a diversity of major events, such as assassinations, civil rights, hip culture, the nuclear arms race, the space race, and the Vietnam War. Images follow themes that include arts, politics, popular culture, science, and daily life such as ads for beauty aids, cars, cigarettes, and liquor during a period of rising consumerism that encouraged people to buy the American Dream.

Regardless of who first captured them; all the pictures were treated to the same procedures. This involved researching and obtaining images; photographically isolating and altering specific content by utilizing a variety of cameras and lenses under controlled lightings methods, such as daylight, florescent studio lamps, flash, and electronic ring light. Contact sheets were made and labeled; images were selected to be proofed; images data were cataloged into Lightroom. Next, in Photoshop, each image was set into a black vignette, harkening back to how a lens forms an image, which in turn frames, separates, and focuses attention on each individual picture. These were then adjusted to custom profiles, printed in pairs, similar to a stereo card, and then outputted twice. When complete, the same image appears in all four sides of the cube. The final images were trimmed; tagged with an ID; stamped with an artist chop (signature); folded; and finally placed in a plastic cube.

The Cubes

The cubes reflect the fundamental principle of how digital images are formed by square pixels. Each picture block is a discrete, moveable frame that when linked fashion a complex and varied representation based on modularity. This practice reverberates with street photography in which accidental factors and a prepared mind deliver unforeseen results.

One cannot will spontaneity, but one can introduce unanticipated factors with scissors or a moveable cube. The juxtaposition of the cubes keeps the meaning of individual images on the move, by changing it, hiding it, multiplying it, and ultimately undermining it with no permanent result. This utilization of informed chance actions echoes Brion Gysin’s cut-up method in which text is cut into sections and randomly rearranged, bringing collage into the literary world. The cut up reconfigures the fragments into something new that reveals an unseen aspect of the original by addressing how we live in a world of assembled fragments that unfolds over time. My modified Dream Machine pays homage to these ideas that Gysin experimented with in the 1960s.

Purpose, Time & History

My photographic involvement revolves around my appetite for visual culture. The incorporation of thousands of cubed images make excess an integral part of the piece. The installation embraces the doctrine of skepticism by suggesting that instead of cherry-picked, nostalgic fairy tales, our cultural myths should reflect a wider reality. The pictures were incorporated from disparate realms to generate a complex dialogue of quotes, references, and appropriations, all with a tip of my hat to their source. Ultimately, larger-than-life characters, worlds in conflict, and suspension of disbelief merge to make images playing off the tension among reality, fantasy, humor and drama.

Time is an implicit project theme. We see and learn in time. Each photograph not only presents its own historical reference, but how it was perceived when it was recreated, and interpreted by each observer. The nonlinear, stream of consciousness flow of images invites viewers to look deeply and rethink the past to understand the present so we can make informed decisions about the future.

Conventional histories look for beginnings and endings that form the diversity and randomness of life into structured progressions. Certain facts are put forward while others are ignored. Through their unsystematic placement, the large cube montages scramble this model, allowing images to flow forward and backward in time while being connected to the present. Audiences do not merely consume images but, like a Rorschach test, build and rebuild them. This re-seeing process underscores how meaning is personal, flexible, and in flux.

Such an ambiguous, open-ended approach emulates how the paradoxes and puzzles of our own memories are constructed. Their non-analytic nature can convey a never-ending and ultimately unknowable tale about humanity that exists outside of chronological time. It is this flexibility that gives photographs their strength, allowing them to bend, change, and transform without breaking, making each image alive with possibility. They do not tell us what to feel or think. Instead they evoke a visceral, emotional, point of discovery that asks one to dig deeper and come up with your own telling. It brings to mind Oscar Wilde’s remark: “The moment you think you understand a work of art, it’s dead for you.” Fantastic images are living entities that repeatedly draw viewers back to them because they can reveal things you don’t know or see were there until you need to know them.

|