|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The essential Rogovin: An in-depth conversation

By Robert Hirsch

From Buffalo Spree Magazine, November 2004 V 38/N 7

In the early 1970s, photographer Milton Rogovin made a series of portraits that featured working-class people who lived near his downtown Buffalo optical business. At the suggestion of his wife, Anne, Rogovin returned to photograph the same people in the early 1980s and again in the 1990s. The resulting photographs were published as Triptychs: Buffalo’s Lower West Side Revisited (1994).This condensed time capsule allowed viewers to witness how the people in Rogovin’s photographs had changed and endured over time. Rogovin refers to his subjects as the “forgotten ones,” because they are overlooked by society and do not possess power or a voice. Forging his socially conscious position from the human economic and political struggles he experienced during Great Depression of the 1930s, Rogovin hoped that by photographing the “forgotten ones” he could create a basis for compassion and fair treatment. Rogovin’s photographs have been internationally admired, collected, and exhibited, and are in major museum collecions nationwide. In 1999, 1200 of Rogovin’s photographs were acquired by the Library of Congress, and the Burchfield-Penney Art Center’s large collection of his work has been packaged into a national touring exhibition entitled Remembering the Forgotten Ones, which appeared at the New York Historical Society in 2003.

For this interview, Rogovin met with me numerous times in the living room and kitchen of his long-time family home in North Buffalo, where the dining room table is buried under photographs and the walls are covered with pictures.

Robert Hirsch: Tell us about your family background.

Milton Rogovin: My parents, Jacob and Dora, came to America as immigrants and set up a store that sold household goods in New York City, where I was born in December 1909. In 1931 the Great Depression forced the store into bankruptcy.

What brought you to Buffalo?

I graduated from Columbia University as an optometrist in 1931, just four months after my father died. Work was very scarce and sporadic. I came to Buffalo for work in 1938 and established my own practice the following year.

How did the Depression politicize you?

The loss of my father’s business, his death, and the concrete events I witnessed of people suffering everyday during the Depression completely changed my thinking... I felt that it was not enough just to feel these things, and that I had to do something to help change the situation. I could no longer be indifferent and, like many others at the time, I worked for a better future through socialism. I read books by political activists, such as Michael Gold’s Jews Without Money (1930) and Change the World (1937), and numerous essays by Emma Goldman, which confirmed my feeling that changes were necessary and we had to do it ourselves.

|

|

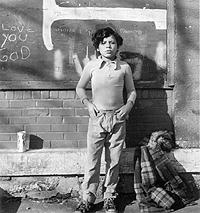

From Triptychs: Buffalo’s Lower West Side Revisited: Edwin Santiago, 1973

Photo by Milton Rogovin.

|

Tell us about your involvement with the workers’ rights movement during the1930s.

I became involved in left-wing politics and was active in organizing the Optical Workers Union in New York City. I continued this work in Buffalo and helped to reorganize the disintegrated local optical union here. Most optometrists did not look favorably on my activities [laughs]. I picketed two of my boss’s offices [laughs] and that was the end of my job. I had union following and I decided to open my own optical office on Chippewa Street, at the edge of Buffalo’s Lower West Side.

How did meeting your wife and your interest in photography intersect?

I met Anne [Setters] at a wedding reception in Buffalo while discussing the Spanish Civil War... We were married in 1942, the same year that I bought my first camera and was drafted into the U.S.Army and went overseas... It was not until about fifteen years later that I really started to make photographs.

What was your first photographic project in Buffalo?

It was the storefront church series that I began as a way of speaking out through photography about the problems in our society. W.E.B.DuBois (a founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) encouraged me to do this series, and he later wrote an introduction for this work.

How did a white guy with a Jewish background get interested in storefront churches?

MR: [laughing] Bill Talmage, a friend of mine who taught music at Buffalo State College, asked me if I would take photographs while he was recording the music at these churches. We worked together for three months and he completed his series.I stayed on to do an in-depth study. Every Sunday for three years I went to these little storefront churches. They got to know and welcome me and I always gave everyone pictures.

How did Rochester-based photographer Minor White influence your early work?

Before I knew Minor White [who had been an assistant curator at George Eastman House, was teaching photography at Rochester Institute of Technology, and was a founder and first editor of Aperture], I didn’t know how to capture motion. I had a fixed 1/125 of a second notion about photography. When I showed Minor my work, he suggested that I slow down my shutter speed to 1/25 of a second so I would capture the sense of movement. I continued sending him my photographs and he kept advising me...I stayed at his home for a two-week workshop during which he showed me how to do better darkroom work, which was very important since I never had any lessons. White published over thirty of these photographs in Aperture (1962), which for a rank amateur was very unusual.

What photographic project came next?

I began to photograph for the miners series in Appalachia during 1962 and returned to the mining area over nine summers. In 1983 this work continued with funding from the W. Eugene Smith Memorial Award for Humanistic Photography. With this grant I decided to expand the project to include miners of China, Cuba, Czech, France, Germany, Mexico, Scotland, Spain, the United States, and Zimbabwe. Whenever it was possible I photographed the men and women workers, both on the job and at home with their families.

What other artists influenced your artistic vision?

Photographer Margaret Bourke-White and the Farm Security group, especially Dorothea Lang and Walker Evans, influenced me as well as the social documentary work of Lewis Hine. In addition, I was friends with photographer Paul Strand. Strand and I shared many similar concerns and he moved to France in the early 1950s because of his political beliefs. I stayed in touch with Strand, sending him photographs on a regular basis and visiting him when he would return to New York.

Why were you called before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1957?

My union activities and the fact that I was the librarian of Buffalo’s communist party brought me to the attention of the committee and the FBI. I had a very difficult time getting a lawyer to represent me. When I appeared before the Committee I invoked my constitutional right not to testify.

What happened to your life after that?

When the McCarthy committee got after me, the local newspapers labeled me “Buffalo’s Top Red.” My optometry business was immediately cut in half. We were shunned. Neighbors refused to allow their children to play with our children. It was terrible.

What motivated you to start making the photographs that eventually became the Buffalo’s Lower West Side project?

Since my voice [as a political activist] was essentially silenced I decided to speak out about problems through my photography. Ordinary people interested me and I wanted someone to pay attention to them. I began to phase out my optometric practice and concentrate on photographing the residents of Buffalo’s Lower West Side. My practice was located close to this former working-class Italian neighborhood, which had become home to African-American, Puerto Rican, Native-American, and poor white families. The area has high rates of unemployment, alcoholism, drug use, and prostitution.

I wanted to make sympathetic portraits of the poorest of the poor in our community that showed them as decent human struggling to get by. Most are considered los olvidados, the forgotten ones, who are without a voice or power. Most people don’t even know these people exist. By photographing them, I thought, I do bring them to the attention of the general public that they were people just like us and should not be looked down upon or abused in any way.

The title stems from the Luis Bunuel film Los Olvidados (1950).

What appealed to you about Los Olvidados?

Bunuel made this low budget film in Mexico that explored the extraordinary by using ordinary people and locations. The name just stuck with me and since we were dealing with people in similar situations I kept using the phase “the forgotten ones”.

What were people’s initial reactions to you?

At first I was regarded with great suspicion. People thought the authorities, the FBI, or the Welfare Department sent me to spy on them.

How did you gain their confidence?

In those days, people in such areas were not used to being photographed, or indeed to being given any attention at all...I showed an interest, was polite, and tried to put people at ease. My wife accompanied me and would talk with people. I would come back and give anyone I photographed a copy of their picture a few weeks later. Gradually I became known and trusted...I remained in the area for the next three years.

Were you worried about being robbed?

When I first went and set up my Hasselblad on a tripod, people would ask how much the camera was worth. After this happened a few times, I got the message and came back with my old twin lens Rolleiflex.

What was the general reaction to your project?

After I was accepted, most of the people felt good that someone wanted to photograph them, pay attention to them. Then the Albright-Knox Gallery of Art showed these photographs and this gave me creditability.

Did you consider yourself a champion of the underdog?

No; just like Käthe Kollwitz said, if it were not for the ordinary people I would have given up my artwork. It was the poor people who interested me and I wanted to photograph. I was never interested in photographing the rich.

For me photography was not a way of making a living, but a way to express my thoughts about people. It made me feel good that I could bring the forgotten ones to public attention. I felt I was doing something important. It wasn’t part of the radical [political] approach that I should do photography; it was something I felt I had to do as an individual to make a difference.

Do you think your photographs do have an impact?

Recently the fellow who reads the gas meter told me: “I love your work” [laughs]. I was very deeply moved...When people look at my photographs and books it encourages them to see that there are problems.

Why did you decide on using a square, twin-lens-format camera?

I liked the twin lens format with its waist-level viewfinder because it allowed me to look down into the camera. This was a much better way of making photographs of people as I was sort of bowing in front of my subjects and this creates a different kind of interaction than aiming a camera directly at them. Also, the larger negative allowed me to crop the image in the darkroom.

Why did you choose black-and-white?

If I photographed a woman in a pink dress, all people saw was the pink dress. Color got in the way of what I thought was important, so I got rid of it.

Your subjects are centered within the frame and looking directly into the camera. Is this the result of your structured training as an optometrist?

My photographs are straightforward. I always asked permission before taking pictures. I wanted to get close and make the people be the most important thing in the frame. I never directed them or told them where to stand, how to hold their hands, or what to wear. The only thing I asked them was to look at the camera. I liked it when I saw their eyes and that’s when I knew I was ready to make their picture. Typically I would make 2 or 3 exposures. When you look at these pictures you know that I was not sneaking around trying to steal pictures of people.

What type of lighting did you use for your interior work?

I used a bare bulb flash because it produces a soft even light in all directions.

Did you do your own darkroom work?

Yes; ...for me it was essential to make my own prints in a simple basement darkroom in our house. Who else could know what I saw and how I wanted to show it? [Rogovin has donated his darkroom to the Burchfield-Penney Art Center.]

Tell us about Triptychs: Buffalo’s Lower West Side Revisited.

When I returned to the Lower West Side, at my wife’s urging, in the 1980s and again in the early 1990s, my biggest problem was to find the people and families I had originally photographed. Since I had learned not to ask too many questions, I did not have their names and addresses. I would take a box of photos to the corner where people would gather and show them the pictures. They would tell me who had broken up, who was in jail, who had OD’d, who had died, or moved away; and where I could find those who still lived there. For these reasons, a person might be missing in the second of third photograph of the triptychs.

What role did your late wife Anne play in this project?

When I started making these pictures in 1972, Anne would go out with me and as an activist for peace and justice she got involved with people.She encouraged me to give up optometry and devote myself to photography, which I did in 1975. Her job teaching Special Education supported us. This change to being a full-time photographer enabled me to start the series, Working People, where I went into the Buffalo steel factories during the working day to make pictures. I photographed in both the factory and in the workers’ homes with their families. Some of this work was published in Portraits in Steel, with interviews by Michael Frisch (1993). It was her idea that I should go back and photograph the people again. Also, Anne did not allow television in the house as she thought it was not a good thing to be hooked on TV, and it was more important to do our work.

How and why did you go to Cuba?

I got access by telling the Cuban officials about my work with DuBois and Neruda. I made a number of visits to photograph people working in factories. The last time I photographed nickel miners near Guantanamo. One of the miners invited me to his home to photograph, which resulted in a wonderful series of photographs. I also met the leading Cuban poet Nancy Morejón and this lead to a collaboration in which Nancy wrote thirty-eight poems in response to my Cuban photographs. The result is the recent publication of With Eyes and Soul: Images of Cuba by Dennis Maloney’s White Pine Press here in Buffalo (www.whitepine.org).

What have you done with your negatives and your prints?

The Library of Congress accepted my entire archive of negatives in 1999 and they will be available for future use, including online.Robert and Mary Ann Budin purch ased 225 of my photographs and donated them to the Burchfield-Penney Art Center. In addition, the J.Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles acquired 133 of my photographs.

I understand there’s a short 12-minute film about your work.

Yes, Harvey Wang who accompanied Dave [Isay who produced an NPR segment on Rogovin] made The Forgotten Ones, which won the prize for best documentary short at the TriBeCa Film Festival last year (www.harveywang.com).

I recently saw one of your books prominently offered for sale at the Wegmans supermarket in Buffalo.

MR: Yes, I had a book signing at Wegmans. I like people seeing my pictures in everyday situations. I had mural size photographs of steel workers installed inside Buffalo subway stations. I also have photographs on display at the downtown Buffalo Library and the Columbus Community Health Center on Niagara Street. People come in and see their friends and relatives on the wall. There is even a photograph I made years ago of a fellow who is now the clinic director.

What riles you today?

I recently attended an anti-war demonstration on Elmwood Avenue and Bidwell Parkway because I thought it was important to have one more person speaking out.

What is the best thing about living to be ninety-four years old?

I was forty-seven before I seriously took up photography, so it has allowed me time to continue to do my work, including my poetry.

|

|

Milton Rogovin.

Photo by Jim Bush.

|

And the downside?

I had to overcome heart surgery, prostate cancer, and cataracts. The worst was losing my wife of sixty-three years, Anne. We worked together very closely; she made many contributions to my work, and was a tremendous help in alleviating suspicion of me as a photographer. Here were two nice old characters and people didn’t worry about us [laughs].

How would you describe your spiritual outlook?

I consider myself an atheist. If there are problems, we will have to solve them here and now. We can’t rely on the belief that someone up above will solve them for us. We have to do it ourselves.

What advice would you give to someone starting out in photography?

You must believe in what you are doing. When you run into problems, you must keep plugging away and keep doing it. It is never easy. My slogan is never give up.

For more information, visit www.miltonrogovin.com.

Robert Hirsch is an Associate Editor of Digital Camera and the author of the newly released Exploring Color Photography: From the Darkroom to the Digital Studio by McGraw-Hill (see: http://novella.mhhe.com/sites/0072407069). He has also written Seizing the Light: A History of Photography and Photographic Possibilities: The Expressive Use of Ideas, Materials & Processes, Second Edition.

Back to Top

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|