|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Resurrection of the Photobook

Rob Hirsch talks to Martin Parr about how photography books influence how we make and understand photographs

Interview by Robert Hirsch

From Digital Camera Magazine, N32

Since William Henry Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature (1844 – 1846), photographers have viewed books as the ideal vehicle for delivering their images to a large audience. In The Photobook: A History Volume I (Phaidon Press, www.phaidon.com, £45), Martin Parr and Gerry Badger offer their account of how artist/photographers have used the book format to widely disseminate their vision and how this process has influenced other photographers. Here, Rob Hirsch discusses the nature of the photography book with Martin Parr.

Robert Hirsch: What have photography books taught you?

Martin Parr: For me, the photobook has been an essential learning tool about photography and other photographers.

What is the central premise of The Photobook Volume I?

It was to give the photobook a central place in the history of photography.

How do you define a photobook?

A photobook is a book, with or without text, where photographs carry the principal message. A photographer or photo editor is the author. It has its own distinctive character, which is different from a photographic print.

How were you able to narrow the focus?

We concentrated on photographers as auteurs; those who create according to their personal vision and who consider the photobook an independent art form.

What were your criteria for an outstanding photobook?

To paraphrase photographer and photo bookmaker John Gossage, it should contain a great work and make that work function as a concise world within the confi nes of the book.

How can photobooks expand the history of photography?

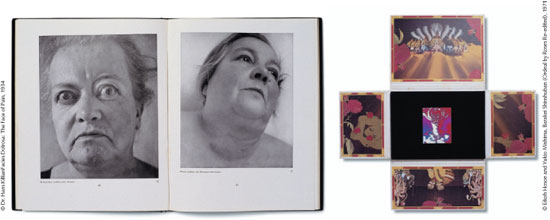

The history of photography has been predominately written by American and European academics and curators who have not ventured far from their shores. There is so much more out there. We cover unusual titles like Owen Simmons’ The Book of Bread (1903) and Hans Killian’s The Face of Pain (1934) to classics such as Henri Cartier-Bresson’s The Decisive Moment (1952). We devote one chapter to the postwar Japanese photobook because the topic has not received the attention it deserves.

Why is the book format so vital?

Photographers are hungry for information on what other photographers have done. This is how photographers inform their practice. We learn from the accumulated photographic culture of photography. When you look at people’s work you can see where the ideas came from and how one thing leads to another. As a practising photographer there are sources and inspiration that have helped me to develop my own vision. It’s almost impossible do this on your own. We need to be informed about the visual ideas and languages of the past.

What about the reach of a book?

More people see a book than see an exhibition. The wonderful thing about a book, instead of an exhibition, is that it’s here forever. Plus books travel inexpensively. A travelling idea if you like. When one opens a book up and looks/reads, it exposes life. That whole process of spreading information combined with the three-dimensional tactile quality of the book is something that appeals to me.

How, over time, do you think books globalise creative photography?

We can observe the infl uence of great books, such as William Klein’s New York (1956) and Robert Frank’s The Americans (1959) on Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1986), which influenced Hiromix’s Girls Blue: Rockin’ On (1996). It takes time for an idea to gel down and for people to understand its importance. It’s part of the process of how photographic culture rolls along and the book is an essential part of that process.

How is digital imaging realising Talbot’s dream of every man being his own printer and publisher?

In The Photobook, Volume II we present Alex Soth’s Sleeping by the Mississippi (2004). Originally Soth made two editions on his computer and printed them out. He showed it around and got it published by Steidl. It’s a good example of how the digital age can help anyone make a book.

What affect will the web and e-books have on the photobook?

I see the web as making books more accessible and more exciting. However, even with downloadable books, I believe people still want something to handle. I wouldn’t buy an e-book - I want a beautifully made touchable object. The book has never been more popular and it will continue to flourish…•

|

Download an Adobe PDF of this aricle : |

|

|

|

|

Back to Top

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|